By Daniella Rose King

Writer and curator

Art Hx 2021-2022 Interpretive Fellow

Under the title Embodied Entanglements, three constellations (Hostile Environments, The Master’s Tools, and Invasive Species) consider the entanglements of racial capitalism, medicine, and the environment. Coalescing around different, yet interrelated themes, the texts are spurred by close readings of a selection of artworks and archival materials. Looking to examples and approaches that reclaim subaltern geographies from which to understand history and our natural environment, the artworks and historical objects—photographs, video, paintings, sculptures, and works on paper—constitute a diverse array of intellectual projects that mobilize alternative framings of value and history, and of relationships to place, labor, and nature.

Invasive Species

The final constellation explores questions of refusal, repair, and remembrance against the backdrop of colonial-botanical explorations and bioprospecting in the Caribbean and centuries of deforestation, monocropping, and ecological devastation wrought by colonialism and extractive capitalism. The works drawn together here decenter and destabilize the existing historical-botanical-geographical records and narratives of the Caribbean and highlight Black and Indigenous knowledges and the role they have played in the foundation of botany and medicine.

Maria Sibylla Merian, Orange-flowered plant, with example of a grey and orange moth, from an album of 91 drawings entitled ‘Merian’s Drawings of Surinam Insects &c’; with blue caterpillar and chrysalis, circa 1701–1705. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The plant featured in this botanical illustration is known in Barbados as the “Pride of Barbados,” our national flower. The leaves, flower, bark and seeds of the plant are poisonous and have been used as an aid for suicide and homicide. Most prominently, the plant was used by enslaved women as an abortifacient alongside other herbal medicines. The plant, and the indigenous knowledge of its properties, played a significant role in practices of refusal on the plantation, a biotic resistance to sexual abuse and reproductive exploitation and disempowerment.

Annalee Davis, Wild Plant Series, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist. Photograph: Mark Doroba

Annalee Davis’s Wild Plant Series (2016) shows studies of botanicals the artist found in former sugar cane fields, drawn onto discarded plantation bookkeeping ledger pages. Many of these plants have medical properties and were used by bush doctors and herbalists to treat a variety of ailments. Davis remarked that she was taught to view the plants as weeds to be eradicated with the use of pesticides. Despite centuries of monocropping, deforestation, and eradication of biodiversity, the plants continue to resurface. And as sugar cane production has waned, fields have been abandoned, and the use of pesticides is being eschewed for organic farming practices locally, native plants are reclaiming the land and re-diversifying the landscape. Similarly, in (Bush) tea plots – A decolonial patch, Davis, in collaboration with landscape architect Kevin Talma and healer, herbalist, and botanist Ras Ils, has cultivated a range of native tea plants, used historically and medicinally as bush tea for the treatment of a variety of issues including reproductive health, whilst also demonstrating a practice of biodiversity.

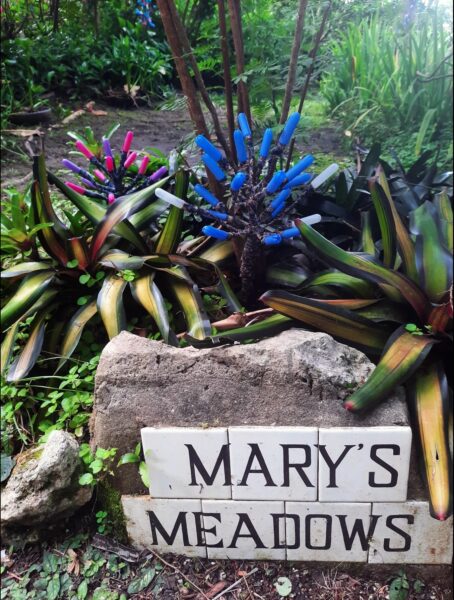

Katherine Kennedy, Invasive Species (in situ), 2020, Barbados Flower Forest Botanical Gardens. Image courtesy of the artist

Works in Invasive Species (2020), Katherine Kennedy’s sculptural series installed throughout Barbados’s Flower Forest Botanical Garden, mimic the forms, patterns, and gestures of the plant life they are embedded within. Composed of found materials, including textiles, beads, wire, and plastic tampon applicators, the works speak to the collision of historical trajectories: colonial bioprospecting, ecological catastrophe, reproductive health, the burning of fossil fuels, and the proliferation of plastic waste. We are told on a near daily basis of the novel frontiers where microplastics are found (most recently in the lining of human lungs).[1] The shiny plastic appendages and woven surfaces of pieces in Invasive Species give Kennedy’s creatures away as not quite natural, not belonging in the landscape, despite their construction from materials that are endlessly piling up in landfills, oceans, rivers, and beaches. The pristine botanical garden, the untouched forest, seem to be the lie—the alien here in our anthropocentric age. Invasive Species draws attention to the intersections of ecological devastation produced by colonization, capitalism and consumerism, reproductive labor, environmental racism, and the body. The clever deployment of an intimate, single-use medical device utilized by millions around the world says much about the porous boundaries between humans, man-made materials, and technology and resulting dependencies. At the same time, the works hint at new species born in the wake of our climate crises, as well as to tendencies that eschew extractive practices of making in favor of working with what is abundant and would otherwise go to waste. These are principles that resist capitalist imperialist consumption and individualism, the relics of plantation economies, in favor of communal, inclusive, reparative means of relating to others and the environment.

[1] Damian Carrington, “Microplastics found deep in lungs of living people for first time,” The Guardian, April 6, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/apr/06/microplastics-found-deep-in-lungs-of-living-people-for-first-time.

Comments are closed