By Dr. Anna Reid

Writer, curator and historian of art

Art Hx 2021-2022 Interpretive Fellow

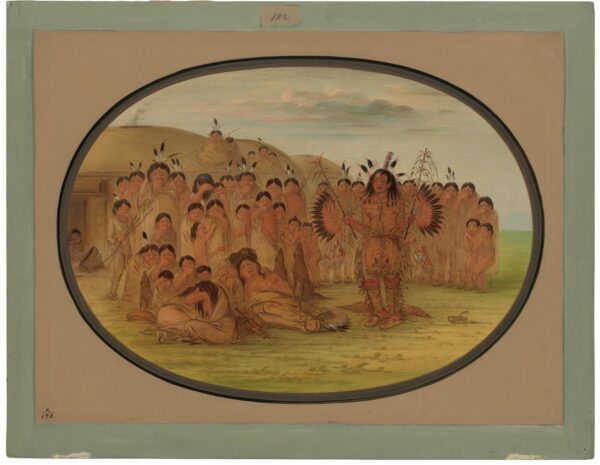

George Catlin, A Mandan Medicine Man, 1861/1869, Paul Mellon Collection, National Gallery of Art, 1965.16.85. Public Domain

I have chosen a set of nineteenth century paintings of Native American people, notably shamanic figures, which visualize complex and intricate spiritual and medicinal practices. Yet these ethnographic portrayals are foremost colonial representations which threatened the very ways of life and healing that they claimed to preserve.

George Catlin, Medicine Man, Performing His Mysteries over a Dying Man, 1832, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr., 1985.66.161. Public Domain

Medicine Man, Performing his Mysteries over a Dying Man (1832) is an evocative portrayal in oil of a shamanic ritual. The armed healer performs in a bear pelt strung with feathers, snakes, and animal skins. The Pennsylvania-born artist George Catlin (1796-1872) made the work during his encounter with the nomadic Blackfoot people in the course of five trips west between 1831 and 1837; the work was made for the purpose of documenting Native people for Catlin’s 1841 book North American Indians.[1]

George Catlin, Mah-tó-he-ha, Old Bear, a Medicine Man, 1832, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr., 1985.66.129. Public Domain

Mah-tó-he-hah, Old Bear, a Medicine Man is another painting of a healer of the Mandan nation made by Catlin in the same year. “Old Bear” is a spectacular figure, painted and adorned with red, green, herb, and props in feather and fur. Catlin returns to the subject in the 1860s, depicting A Mandan Medicine Man with a patient and a captivated group of onlookers displaying fear and awe. These depictions of shamanic figures stand out among the hundreds of works that Catlin assembled into touring “Indian Galleries” then displayed in US cities and in London, Brussels, and Paris.

A North American Indian shaman or medicine man healing a patient is a chromolithograph (plate 46) that is part of a broader set of illustrations by Captain Seth Eastman (1808-1875).[2] Eastman’s depiction of a medicine man shows a tepee dwelling where a patient is laid down beneath a blanket and furs. The shaman—eyes raised to a turbulent sky—wears a decorated tunic and works with a buffalo horn, large bowl, sword, cloth, and rattle, implying singing or chanting. Maine-born Eastman painted and drew scenes of Native American people at Minnesota’s Fort Snelling where he was posted from 1830 and again from 1841. In 1849, Eastman started work on several hundred illustrations for geographer and ethnologist Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (1793-1864) whose Information Regarding the History, Conditions, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States is a six-volume study of Native Americans published in the 1850s.

The figure of the shamanic leader as medicine man is a trope of white European and US literary and artistic imaginations in the context of Britain’s American colonies that predates these early visual representations. Robert Southey’s 1805 poem Madoc makes a complex and evocative portrayal of its charismatic, shamanic Native American protagonist, Neolin, in a fiction derived from accounts of soldiers, settlers, traders, and missionaries. Neolin is a multi-faceted, resistant character, reminiscent of the war chief, Pontiac, who led armed rebellions against British rule from 1763 to 1766.[3] The mythic fictionalization of noble Native medicine men and their mystical, healing rituals in colonial art and literature turned them into spectral, powerful, romantic figures. Yet these representations are produced in the context of violent subjugation such that conversely, by the 1830s, the political force of Native American nations was being eroded and dismantled by colonial policies in Britain’s North America and the early United States.

The impetus to explore and document Native American life can be read in the context of a concerted colonial strategy. The Indian Removal Act was passed by US president Andrew Jackson in 1830. The policy, which forced relocation of Native American nations under the paternalistic premise of safeguarding their health and survival, was framed as an act meant to preserve a purportedly vanishing race; removal was described by the US government as the only alternative to extinction so that “if the Indians do not emigrate, they must perish.”[4] Portrayals of the shamanic figures represent the same logic: the cosmologies of ancient and intricate shamanic healing rituals are imagined as “preserved,” only in oil, as they are presented to be nearing extinction. Catlin’s touring representations of a “dying race” were a touring spectacularization and a commodification of this narrative of disappearance. Notably, he described his artistic endeavors as a monument to himself, and to Native American people. Well rehearsed descriptions of Catlin’s work and of Eastman’s, as original works of ethnology, must be considered in this regard: as part of a strategy to denigrate and remove Native American Nations.

In her An Indigenous People’ History of the United States, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz describes the actions of the US government against Indigenous Nations as commensurate with the definition of genocide as set out in the 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.[5] The Convention referred to “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” Murder, land dispossession, and forced removal of Indigenous children and people by government agencies was carried out against the narrative backdrop of a “dying race” that was “doomed to perish.” Concurrently, disease, carried to North America by white settlers with little understanding or control of it, killed swathes of Native American people. In the 1780s, for example, a smallpox epidemic reduced the Mandan population from 3,600 to 1,250. In 1837, a second outbreak reduced the number of Mandan people to 150.[6]

The calamity associated with this constellation of paintings of medicine men by Catlin and Eastman, following the logic of settler colonialism, also represents gross non-compliance with obligations that the US government itself encoded in treaties forced upon Indigenous Nations. The contemporary Administration for Native Americans, part of the US Department of Health and Human Services, details the legal principle of the “Trust Responsibility”:

Between 1787 and 1871, the U.S. entered into nearly four hundred treaties with Indian tribes. Generally, in these treaties, the U.S. obtained the land it wanted from the tribes, and in return, the U.S. set aside other reservation lands for those tribes and guaranteed that the federal government would respect the sovereignty of the tribes, would protect the tribes, and would provide for the wellbeing of the tribes.[7]

The fulfillment of Trust responsibilities to Native American Nations remains to be realized. The 1921 Snyder Act provided funds for Native healthcare. The Indian Health Service (IHS) has offered primary and emergency care, covering only 60 percent of the healthcare needs of eligible Native Americans; only individuals who are enrolled members of federally-recognized nations can receive care through this agency. The 2021 Stimulus Bill allocated a doubling of funding for the IHS. Yet Native Americans have a life-expectancy 4.4 years below average, and their communities have the highest rates of pre-existing health conditions. In the context of the global pandemic, Native Americans have died of COVID-19 at nearly twice the rate of white Americans.[8]

This set of rich, detailed documentations of Native American medicine men by Catlin and Eastman points to complex indigenous cultural, spiritual, and medicinal practices that have powerful contemporary currency and significance, not least in the way that they speak of a therapeutic relationship to the land. Despite the logic of loss and erasure portrayed here, these healing practices continue to be shared within, and are used to sustain, Indigenous communities. These paintings and illustrations, as colonial representations confluent with an imperial strategy to dispossess and eradicate Native American Nations, are quite removed from the rhetoric of care and preservation invoked by the US government in the treaties that it imposed. In the late eighteenth century the federal government narrated its obligation to provide for the health and wellbeing of Native American people, an obligation that to the present is grievously unmet.

[1] George Catlin, Letters and notes on the manners, customs and condition of the North American Indians Volume 1 (London: Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, 1841), 40-41.

[2] Eastman depicted a scene that might not be appropriate for public viewership. As such, the work is not reproduced here and is pending additional review by the Art Hx team.

[3] Tim Fulford, “Prophets of Resistance: Native American Shamans and Anglophone Writers,” in Transatlantic Literary Exchanges, 1790-1870: Gender, Race, and Nation, eds. Julia M. Wright and Kevin Hutchings (London: Routledge, 2011), 77-99.

[4] Kathryn S. Hight, “‘Doomed to Perish’: George Catlin’s Depictions of the Mandan,” Art Journal Vol. 49, no. 2 (1990): 119-124.

[5] Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (Boston: Beacon Press, 2015).

[5] Kevin Konrad and Elizabeth Fee, “Old Bear: Mandan Medicine Man,” AM J Public Health Vol. 101, no. 1 (2011): 38-39.

[7] Administration for Children and Families,” American Indians and Alaska Natives – The Trust Responsibility, Fact Sheet,” Accessed February 16, 2022, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ana/fact-sheet/american-indians-and-alaska-natives-trust-responsibility.

[8] “How do Native Americans get Healthcare?,” The Economist, April 20, 2021, https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2021/04/26/how-do-native-americans-get-health-care.

Comments are closed