By Daniella Rose King

Writer and curator

Art Hx 2021-2022 Interpretive Fellow

Under the title Embodied Entanglements, three constellations (Hostile Environments, The Master’s Tools, and Invasive Species) consider the entanglements of racial capitalism, medicine, and the environment. Coalescing around different, yet interrelated themes, the texts are spurred by close readings of a selection of artworks and archival materials. Looking to examples and approaches that reclaim subaltern geographies from which to understand history and our natural environment, the artworks and historical objects—photographs, video, paintings, sculptures, and works on paper—constitute a diverse array of intellectual projects that mobilize alternative framings of value and history, relationships to place, labor, and nature.

The Master’s Tools

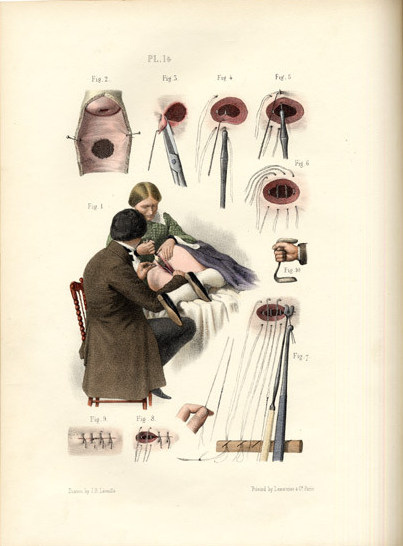

J.B. Léveillé, Dr. James Marion Sims and Nurse Repairing a Vesico-vaginal Fistula Patient, 1870. In Henry Savage, The Surgery, Surgical Pathology, and Surgical Anatomy of the Female Pelvic Organs, in a Series of Coloured Plates Taken from Nature with Commentaries, Notes, and Cases, 2nd. ed. (London: J. & A. Churchill, 1870). Image Courtesy of the Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library, Karolinska Institutet

A small hand-colored lithograph depicts Dr. J. Marion Sims (often called the “father of modern gynecology”) at work on a white female patient. The work, titled Dr. James Marion Sims and nurse repairing a vesico-vaginal fistula patient by Jean Baptiste Léveillé, was published in 1870 in Henry Savage’s The Surgery, Surgical Pathology, and Surgical Anatomy of the Female Pelvic Organs, in a Series of Coloured Plates Taken from Nature. With Commentaries, Notes, and Case. Sims developed surgical tools and procedures largely through experiments on enslaved and poor white (often Irish) women. Three of the enslaved women he named in his diaries as Anarcha Westcott, Betsey Harris, and Lucy Zimmerman were leased to him for five years while he resided in Alabama. He operated on each multiple times without anesthesia. These women’s unimaginable suffering contributed to the development of medical practices, while their torturers spouted enduring racist beliefs that Black women had higher pain thresholds and thicker skins than their white counterparts—beliefs that have laid the groundwork for medical discrimination that is endemic in our contemporary global health systems.

Doreen Lynette Garner, Not only had Sims to close the natural openings in the ravaged vaginal tissues; he had to make the edges of these openings knit together. He opted to abrade or “scarify” the edges of the vaginal tears every time he attempted to repair an opening. He then closed them with sutures and saw them become infected and reopen, painfully, every time., 2016. Image courtesy of the artist and JTT, New York

Doreen Garner’s sculpture “Not only had Sims to close the natural openings in the ravaged vaginal tissues; he had to make the edges of these openings knit together. He opted to abrade or ‘scarify’ the edges of the vaginal tears every time he attempted to repair an opening. He then closed them with sutures and saw them become infected and reopen, painfully, every time” (2016) takes the subject of Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy’s torture and objectification. The title, described in Harriet A. Washington’s 2006 book Medical Apartheid, expounds the extreme pain inflicted by Sims’s surgeries and is an uncomfortable accompaniment to an equally disturbing visual experience. Appearing like an oversized microscope slide, where a cross-section of a body is presented for optimal observation, materials including silicone and fabric create a convincing stand-in for tissue and skin, with excessive stapling suturing the flesh into a monstrous wound.

Doreen Lynette Garner, Vesico Vaginal Fistula, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist and JTT, New York

In Vesico Vaginal Fistula (2016) from the same series, Garner presents an isolated fistula (an abnormal connection between two organs or vessels, in this instance, the bladder and vagina) in a mirrored case that references histories of display, the medical gaze (not to mention the internal visual access granted by Sims’s speculum, for example), a carnival house of mirrors, as well as a sort of reverse panopticon, with the fistula keeping watch at the center. In both works, Garner forces her audience to grapple with the very abject, very painful reality of these individuals’ experiences at the hands of Sims and countless others. Chattel slavery relied upon the transformation of humans into subhuman objects, a project that was bolstered by eugenics and contemporaneous medicine that insisted upon racial-biological hierarchies and theories of difference and inferiority.

Doreen Lynette Garner, Vesico Vaginal Fistula, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist and JTT, New York

In Garner’s work, the multiple procedures and dehumanizations are accumulated in one grotesque form, giving shape to the women’s collective torment. By presenting a vision of historical bodies that have been mutilated, destroyed, experimented upon, and otherwise hidden from the collective imagination, Garner animates Lucy, Anarcha, Betsey and other nameless women’s pain, sacrifice, and existence. Audre Lorde’s proverb that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” brings into view the apparatus, equipment, and surgical tools used cruelly by the “master” on the enslaved as instruments of harm and troubles the ethics and impartiality we expect of the medical sciences, exposing the racism and misogyny at its core.[1]

[1] Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley: Crossing Press, [1984] 2007), 110-114.

Comments are closed