By Joseph Litts

PhD Student, Princeton University and Art Hx Lead Graduate Research Assistant

The Art Hx framework for “Medicalized Space” takes a broad perspective to consider how individuals have chosen to map medicine onto humans and environments to justify exploitation. Simultaneously, multiple histories of radical care interrupt these trajectories of settler colonialism. The materials explored through this framework highlight obscure links between spaces, health, and well-being. We research this past so that we might understand the present—and importantly—so that we might collaborate toward a better future.

For me, “space” is first and foremost another word for “building.” “Medicalized space” reminds me of hospitals, dentist offices, and other places where sick people might be treated and cured. Ideas about sickness and health are culturally specific, of course. Sometimes, these spaces of care have furthered settler colonialism. An example might be found in this 1940s photograph below. In it, a nurse draws blood in an institutional setting.

Frank Royal, Nurse Takes Blood Sample from Boy at the Indian School, Port Alberni, B.C., during a Medical and Dental Survey Conducted by the Department of National Health and Welfare, 1948. Credit: F. Royal/National Film Board of Canada/Library and Archives Canada. Public Domain

This image is from a group of photographs that document pseudo-scientific nutritional experiments at Canada’s residential schools. The Canadian government created this school system (active from 1894 to 1947) to forcibly remove Indigenous children from their homes and assimilate them into Euro-Canadian culture. A key component of this program was the dislocating effect of the new space. Tens of thousands died, in part due to malnutrition masked as science and a place of bodily and psychological harm masked as a school.

The nutritional experiments across Canada involved selectively starving First Nations children. Doctors then observed the effects of various vitamin deficiencies, measured through blood samples. The experiments produced no meaningful knowledge and caused great suffering. Yet, as Ian Mosby has shown, the Euro-Canadian doctors in charge considered the experiments to be a form of care. These doctors claimed that the residential school system was a healthful, medical space. This image and this historical moment are an example of the links between space, place, environment, colonialism, and healthcare that Art Hx seeks to investigate through the “Medicalized Space” framework.

* * *

Writing this introduction leads me back to my question: “How do I know that a space is medical?” I am based in the United States, and here, signs with words like “doctor,” “hospital,” and “urgent care” offer a clue. But there are more covert ways a space could indicate that it is medical. The design and furnishings of a space can signal its uses. Many academy-sanctioned medical spaces I’ve visited in the US have diffused, fluorescent lighting. Vinyl upholstery that can be easily disinfected. People in pale green or blue uniforms. White lab coats. Chrome, glass, steel, and rubber. These are materials that can indicate industry, hygiene, and modernity. Something like the operating room in this clip from Grey’s Anatomy:

Of course, this answer to my question is also culturally specific, and the spaces I’ve just described are common, but also Euro-centric.

A space might be medicalized because of its spiritual significance. It might be medicalized because it is where healing rituals and/or rites of passage are performed. Many of these spaces can be temporary or part of a broader geological landscape. Examples could include amaboma (shelters made of grass in South Africa) or Uluru (a significant landmass in Australia). Out of respect for the traditional owners of these knowledges, we do not reproduce images of many of these spaces. Making or circulating images of them can be sacrilegious.

The answer to my question also depends on how one defines “space.” “Space” can be a synonym for “building,” of course, but it can also refer to a broader place. A broader medicalized landscape might be found among various summer vacation destinations for the wealthy in Europe and North America. One might think of affluent city dwellers fleeing urban spaces for the seashore or mountains during the summer—the opening premise for Billy Wilder’s film The Seven Year Itch (1955). This seasonal migration is an exercise in elite solidarity. However, it has been justified under the guise of seeking healthier air.

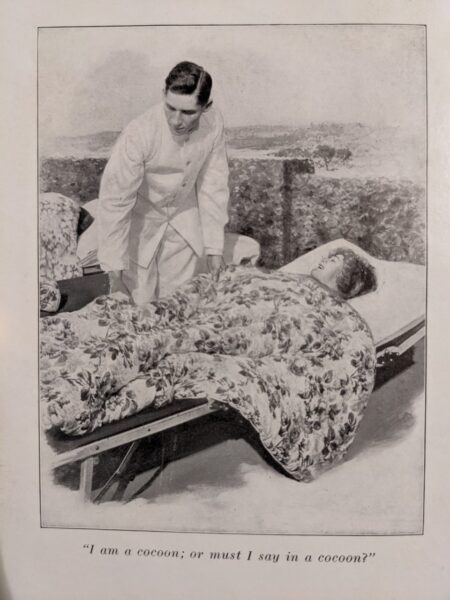

Frontispiece in The cocoon: a rest-cure comedy by Ruth McEnery Stuart (Toronto: McClelland, Goodchild & Stewart, 1915). Public Domain Mark

From this perspective, can sanatoriums in the Swiss Alps or Arizona be considered “medicalized spaces”? Specific environmental qualities—high elevation, low humidity, and bright sunshine—led to building luxurious structures to achieve a health goal of better breathing. This ideal climate happens to coincide with vacations. Today, one might call these sanatoriums merely resorts for wealthy tourists, but they were built to facilitate healing from tuberculosis (then called consumption) due to their relationship with a broader landscape. The 1915 novel The Cocoon: A Rest Cure Comedy exaggerates this tension between recovery and holiday. The book’s frontispiece shows a smiling woman asking her white-jacketed attendant how she should describe her rest cure. She is reclining under a chintz duvet in a clipped box garden. The novel casts this manicured terrace as a medical space, improbable as this may seem.

Davos, Switzerland, and Tucson, Arizona, have thus become famous for their supposedly healthful climates. Simultaneously, other places have become infamous for harboring disease. Many of these places are around the Equator, as this map and public health feature published in a 1944 issue of LIFE indicate.

“The World Shewing the Geographical Distribution of the Human Species” in Crania americana or, A comparative view of the skulls of various aboriginal nations of North and South America: to which is prefixed an essay on the varities of the human species by Samuel George Morton, (Philadelphia: J. Dobson, 1839). Public Domain Mark

This map was made in 1839 to illustrate Samuel George Morton’s Crania Americana, a pseudo-scientific treatise on human variety. In this image, racial difference is created and maintained by tying false ideas about race to landmasses. Morton linked the two through a contrived equation of skull shape and size. Morton took many of these measurements under the guise of providing medical care. His book had an uneasy, close relationship with the medical establishment. This is an example of the ways the broader landscape has been medicalized, in this case for nefarious ends.

* * *

What—where—are medicalized spaces?

Through this Art Hx framework, we begin to understand not only the experiences and uses of medicalized space, but also representations of such spaces with essays, close looking exercises, and object lessons. We illuminate hidden or undiscussed links between care and space. Not all of these are benign. And some spaces advertised as “healing” might have had the opposite effect for those who passed through them, like the Port Alberni residential school.

Art Hx seeks to show the relationships between politics, health, design, landscape, the environment, and architecture. We look to the past to understand the complex lived realities of the present and to imagine possibilities for a better future.

What kinds of spaces might offer better, alternative forms of health or care? As you navigate through the site and our digital content, we welcome you to imagine with us.

Comments are closed