By Dr. Keren Rosa Hammerschlag

Senior Lecturer, Art History and Curatorship, Centre for Art History and Art Theory School of Art and Design, The Australian National University

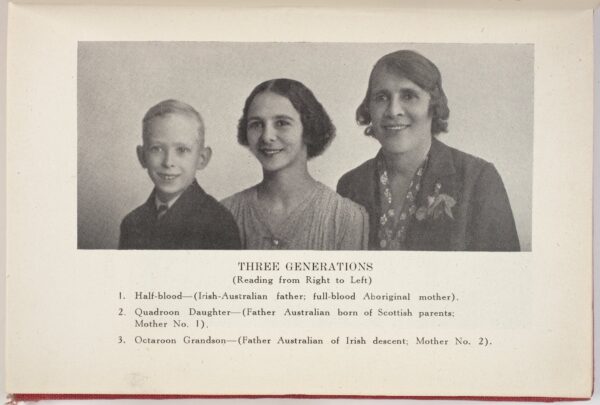

Neville, A.O. “Three Generations.” In Australia’s Coloured Minority: Its Place in the Community, n.p. Sydney: Currawong Publishing Company, 1947. Image courtesy of Museums Victoria. Public Domain.

“Three Generations” is a photograph from Australia of three members of the same family. According to the descriptive text, the image shows individuals characterized as the following: 1. Half-blood—(Irish-Australian father; full-blood Aboriginal mother); 2. Quadroon Daughter—(Father Australian born of Scottish parents; Mother No.1); 3. Octaroon Grandson—(Father Australian of Irish descent; Mother No.2). “Half-blood,” “Quadroon,” and “Octaroon” were pejorative terms used during the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth to qualify ethnic difference by categorizing people of mixed racial descent. In “Three Generations,” as we progress from right to left, from grandmother to mother to grandson, complexions become lighter and features more “European” according to racialized definitions of the day (i.e. an upright forehead, straight nose, fair complexion, etc.). A resemblance persists across the generations, but the “octaroon” grandson exhibits thin blonde hair and light-colored skin—his Aboriginality having apparently been bred out. In other words, the photograph celebrates eugenics policies that promoted “breeding out the colour” from families, such as this one, over time.[1]

For several leading white anthropologists of the period, white European settlers and Indigenous Australians constituted maximally distant racial groups. Their admixture in a place like Australia, “at the extremity of the world,”[2] to use French anthropologist Paul Broca’s phrase, constituted a test case for the hypothesis that the different “races of men” constituted entirely different species and therefore could not reproduce. In On the Phenomena of Hybridity in the Genus Homo, translated from French into English in 1864 by the Anthropological Society of London, Broca described what he viewed as the unsuccessful attempts on the part of the colonizing English to instruct, educate, and civilize Indigenous Australians, emphasizing that these efforts were largely directed at children. In the end, Broca racistly concluded that the Australians were so “savage” that they were beyond elevation.

There was also a line of thought that held sway from the 1890s until the 1940s that Australian Aborigines were prehistoric forerunners of the Caucasians of Europe. The idea that Indigenous Australians were prehistoric Europeans was used to justify official policies of assimilation in Australia. These policies involved the forced removal of “half-caste,” or mixed-race, children from their parents, relatives, and communities. In Australia’s Coloured Minority: Its Place in the Community (1947), author A. O. Neville, the so-called chief protector of Aborigines in Western Australia, based his arguments for racial assimilation on the claim that Aboriginal people “pre-date us in some vague Caucasian direction.”[3]

Notoriously, Neville argued for the forced relocation of all “half-caste” children to residential schools, separating them from their parents and communities. In what constitutes one of the most chilling moments in Australia’s Coloured Minority, Neville writes, “You will have a struggle to get the children away … but believe me they will thank you in the end.”[4] What “end” is he referring to? Despite the language of benevolence that pervades Australia’s Coloured Minority, the practices described amount to a state-sanctioned policy of extermination. This is precisely what is pictured in the photograph “Three Generations.” Appearing as an illustration in Neville’s Australia’s Coloured Minority, the photograph shows all three family members smiling, framed as seemingly happy with their racial evolution. But this is a deceptive façade. The photograph’s visualization of a happy mixed-race family masks the emphasis Neville placed in the text (and in life) on breaking apart Indigenous family units—of breeding out “Australia’s Coloured Minority” in just “Three Generations.”

[1] The phrase “breeding out the colour” refers to the racist policy of “absorption” which was pursued as a solution to the “half-caste problem” in Australia between the wars. In the words of Russell McGregor, “breeding out the colour” was “a stratagem to erase ‘colour,’ to bleach Australia white through programs of regulated reproduction.” “ ‘Breed out the Colour’ or the Importance of Being White,” Australian Historical Studies 33:120 (2002): 286.

[2] Paul Broca, On the Phenomena of Hybridity in the Genus Homo (published for the Anthropological Society, by Longman, Green, Longman, & Roberts, Paternoster Row., London, 1864), 45.

[3] A. O. Neville, Australia’s Coloured Minority: Its Place in the Community (Sydney: Currawong Publishing Co., 1947), 63.

[4] A. O. Neville, Australia’s Coloured Minority: Its Place in the Community (Sydney: Currawong Publishing Co., 1947), 176.

Comments are closed