By Michelle Millar Fisher and Amber Winick, Designing Motherhood

Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births. Photo: Erik Gould. Image courtesy Designing Motherhood.

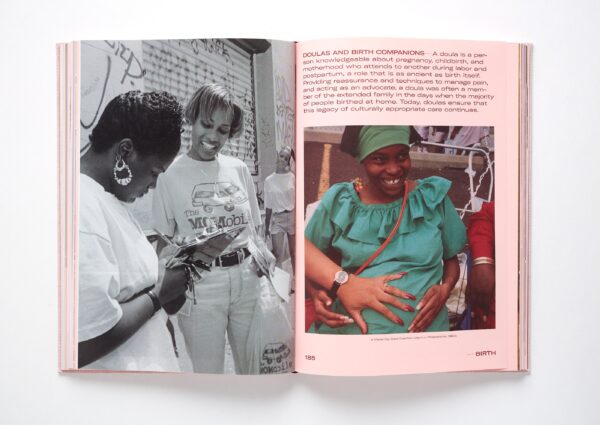

Maternity Care Coalition staff serving their clients in Philadelphia, 1980s. Photo by Jerry Millevoi. Courtesy of MCC and the University of Pennsylvania Library Archives (MSColl760, Box 44, Folder 56)

We’re a couple of design historians who have had the joy and privilege to work with a team of incredibly talented and committed people on a multi-part project called Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births. At the heart of this team are the direct service staff—birth advocates, doulas, lactation and early childhood and childcare experts—of community organization Maternity Care Coalition (MCC).

Since 1980, MCC has worked in southeastern Pennsylvania to improve the health and well-being of pregnant people and parenting families, focusing particularly on neighborhoods with high rates of poverty, infant mortality, health disparities, and changing immigration patterns. MCC’s work focuses on programs that anticipate and address community needs through a continuum of maternal and family health home-visit interventions including their MOM Mobile program of home visitors and their in-community doula training program. Theirs is literally life-and-death work. The United States currently has the highest rate of maternal mortality in any high-resource country, which skews even higher for birthing people of color, particularly and precipitously for Black and Indigenous individuals.

Postpartum faja wrap, California. Image courtesy of Sophia Harris

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the medical journal The Lancet define midwifery as “skilled, knowledgeable and compassionate care” for childbearing people and their infants and families. Until the first quarter of the twentieth century, birth took place at home, largely attended by midwives from local communities. In the United States, the practice of midwifery was rooted in shared skill and wisdom, especially the expertise of Indigenous, and later Black, women. Likewise, immigrant women to the US, like those from Ireland, possessed and maintained midwifery and home-based health-care practices from many cultural backgrounds.

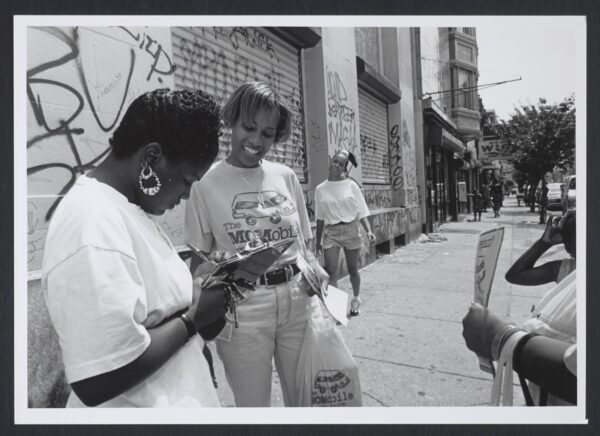

Our Bodies, Ourselves, second edition c. 1973. Photo: Erik Gould. Image courtesy Our Bodies, Ourselves

As hospital birth proliferated in the US in the twentieth century, university-trained doctors, most of whom were white men, usurped the role of the midwife, and many of the culturally appropriate care practices that midwives brought to birth were lost. One of the hallmarks of the midwifery model of care is meeting birthing people where they are. Today, around ten percent of US births are midwife-attended compared to more than fifty percent in other high-resource countries. The WHO and other international global health experts recommend one simple way to improve maternal and newborn outcomes, reduce rates of unnecessary interventions, and realize cost savings: create more pathways for birthing people to access the midwifery model of care.

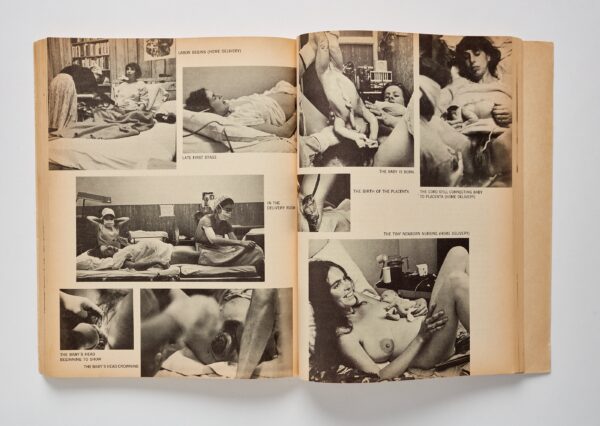

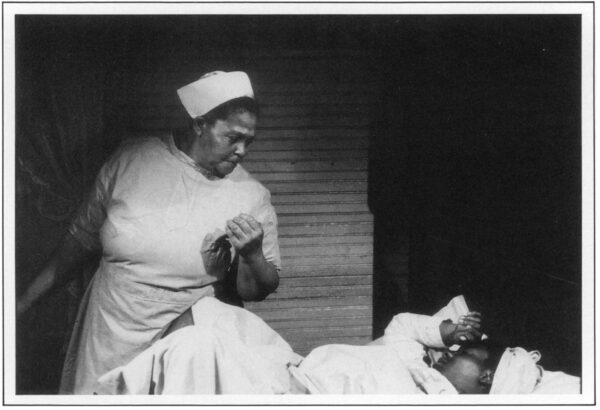

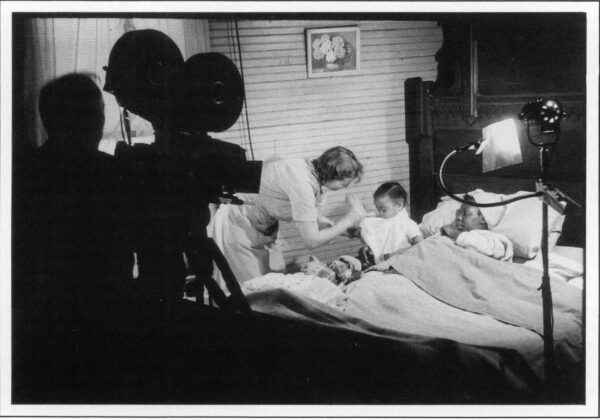

Still from the film All My Babies, directed by George Stoney, 1953, and highlighting the work of midwife Mary Francis Coley. Georgia Department of Health, Atlanta.

All My Babies: A Midwife’s Own Story, a film featured in one of our exhibitions, beautifully demonstrates the power of midwifery in local communities. The film was released in 1953 as a training aid for midwives and other health professionals at a time when birth was moving from the home to the hospital. It depicts the critical role of Black midwives in communities across the US American South. Commissioned by the Georgia Department of Public Health, filmmaker George C. Stoney shadowed midwife Mary Francis Hill Coley for four months in Albany, Georgia. The brief from state officials was to include 118 separate topics within the film, like managing relationships between the midwife and public health specialists, breathing techniques during labor, and incorporating partners and siblings into the birthing process.

Still from the film All My Babies, directed by George Stoney, 1953, and highlighting the work of midwife Mary Francis Coley. Georgia Department of Health, Atlanta.

Stoney was partially inspired by the work of Italian neorealist directors, whose films of the 1940s and early 1950s were shot on location using nonprofessional actors and foregrounded the stories of the poor and working class. The director was also inspired by the evocative photographs of Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and others who documented the Great Depression for the Farm Security Administration, an agency created by the New Deal. While some acting was involved, actual homes, streetscapes, and medical offices were the backdrops for prenatal exams, and the film centers on—and shows in detail—two births that Coley attends with skill and high standards of hygiene. Filmed during the Jim Crow era, the documentary records the uncomfortable and enforced deference of Black midwives interacting with white doctors and nurses at the county clinic, and it even shows Coley questioning her own excellent hygiene practices after a group lecture by a white doctor.

All My Babies foreshadows the demise of Black midwifery that once provided critical care for poor and rural pregnant women of all races throughout the US American South. Indispensable within their communities, Black midwives passed their knowledge down through generations during the institutionalized racism and violence of slavery in the antebellum period. Black midwives were also crucial during segregation; at a time when Black women were often denied admittance to hospitals, midwife-attended home birth was frequently the only viable option for Black families. The film paints a rare portrait of how Coley’s model of care coexisted alongside the growing medical-industrial complex and of how Black midwives and their patients worked within a racist medical system.

The following are a handful of other excellent historic accounts of Black midwifery and birth advocacy: Onnie Lee Logan (1910-1995), Motherwit: An Alabama Midwife’s Story (1989); Margaret Charles Smith (1906-2004), Listen to Me Good: The Life Story of an Alabama Midwife (1996); and Gladys Milton (1924-1999), Beyond the Storm: An Extraordinary Journey (1997).

Margaret Charles Smith worked as a granny midwife in Greene County, Alabama. She obtained her midwife permit—which required passing an examination and registering under the State Board of Health—in 1949. In 1976, Alabama passed a law that ended the issuance of midwife permits to women not professionally trained and registered as nurse-midwives, which meant the collapse of the “granny midwife.” Smith attended her last birth in 1981.

Like the story of Mary Francis Coley in All My Babies, Smith’s Motherwit: An Alabama Midwife’s Story is a firsthand account of a Black woman who provided women in her community with experienced obstetrical care. She was discriminated against by the oppressive Jim Crow laws enacted by the southern states even after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. However, her work gave nearly three thousand women a voice in their birthing process and agency to make well-informed decisions regarding care during pregnancy and through delivery.

In 1944, the Alabama Bureau of Child and Maternal Health found that Black women who attended prenatal clinics and had midwife-supported births had a 9 percent lower maternal mortality rate and a 35 percent lower neonatal mortality rate than white women who received private medical care. (Today, with most births in hospitals, that statistic has flipped with Black maternal and infant mortality rates in Alabama more than double that of white communities).

Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births. Photo: Erik Gould. Image courtesy Designing Motherhood

In the twenty-first century, Black midwives and doulas provide a new generation of birthing people with expert advocacy and care across the United States. As Tekara Gainey, a MCC doula with whom we were lucky enough to work with as an advisor throughout the Designing Motherhood project noted in her interview in the Designing Motherhood book, “Every individual was birthed by someone. We all went through this process … So approaching birth with compassion and love can be healing. It seems like such a simple and commonsense thing to do, but for some reason we’ve gotten away from that. We’ve gotten away from respecting birth as a physiological, normal process … We need to get back to … birthing folks with compassionate care. Because it is the hardest, the most challenging, the most transformational process anyone will ever go through.”[1]

[1] Tekara Gainey quoted in “Doulas and Birth Companions,” in Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births, eds. Michelle Millar Fisher and Amber Winick (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2021), 188.

Comments are closed