By: Sadie Levy Gale, 2022-2023 Art Hx Interpretive Fellow

Visual propaganda was instrumental to the burgeoning of tropical medicine as a discipline in twentieth-century Britain. Images that projected visions of Britain’s advances in tropical medicine circulated across the British Empire, participating in and reinforcing colonial discourses of health that framed Britain as the imperial centre of biomedical knowledge and technology. Placing three images concerned with colonial medicine, the environment, and public health in dialogue with each other, this constellation uncovers how they share an emphasis on practices of looking and “the expert gaze,” a visual rhetoric that presented British medical authority as innate and research on colonial medicine as a necessity. Produced at the turn of the century and across the first half of the twentieth century, these images were intended for public circulation, created to promote British efforts to eradicate tropical disease when colonial medical research was at its height. Yet reading these images against their perspectival bias can destabilise the centre-periphery model of relations that underpinned discourses of colonial medicine. I return to one of these images and read past its ‘immediate’ content to consider how colonial medical knowledge in fact circulated through what Roberta Bivins calls “fluid and multilateral networks of exchange” that were informed and shaped by both colonising and colonised cultures.1

In 1899, British artist W.T. Maud produced an illustration for The Graphic, a popular weekly illustrated magazine that circulated in Britain and had subscribers across the British Empire. Captioned “Professor Boyce and Professor Sherrington examining malarial microbes,” the illustration was printed alongside an article entitled “The Treatment of Tropical Diseases,” which detailed the circumstances of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine’s opening that year. Together, the text and Maud’s illustration work to frame medical vision and the right type of “looking” as central to the conquest of tropical disease. As the author (who is unnamed) puts it, “diseases to be known must be seen.”2 This sense of the ultimate authority of medical vision—particularly when the gaze belongs to a white British medical professional—is everywhere in Maud’s illustration. It pictures Sir Robert William Boyce, the Dean of the School of Tropical Medicine, peering into a microscope, while Charles Sherrington, Professor of Physiology at Liverpool, and Sir Ronald Ross, a lecturer in Tropical Medicine at the School (who would go on to win the Nobel prize for identifying how malaria was transmitted) look at each other as they confer behind Boyce. Other figures in the background are depicted watching the three experts at work.

A double gaze operates in this image, in which the gaze of the scientists watching Ross and Sherrington in the laboratory is echoed by the viewer encountering the illustration in the pages of The Graphic; Maud’s illustration is fundamentally concerned with instructing the viewer about the right way to “look.” The dramatized gaze of the medical men—along with their formal suits, posed concentration and use of tools like the microscope—can be read as a highly staged rendering of the superiority of colonial frames of vision. Maud deploys these visual tropes to project a vision of the archetypal “medical expert.” His illustration suggests that, so long as the knowledgeable gaze of the medical man is replicated, the health of colonial populations and the longevity of the British Empire will prevail. Tellingly, the article’s author views the vanquishment of tropical disease as instrumental to ensuring that “tropical countries will in a measurable time be made habitable by the white man.”3 The gaze, then, is also racialized, operating only for the benefit of improving the health of white British populations. Maud’s illustration would have intended to naturalize and justify racialized conceptions of who should have access to healthcare for The Graphic’s white middle-class readers.

The sartorial elegance of the medical men, the performance of multiple types of looking, and the laboratory setting exemplifies a recurring visual pattern in much twentieth-century visual culture concerned with tropical medicine. For example, a photograph taken by Norman Kingsley Harrison (a photographer for Topical Press, a British news agency) of the new bacteriology department at Guy’s Hospital Medical School in 1938 pictures scientists at work in “one of the finest research centres in the Empire,” according to the caption.

The photograph is visually similar to Maud’s image; the scientists (wearing white lab coats in place of suits) are depicted studiously gazing into microscopes, with lab tools arrayed around them. The careful composition of the photograph—which draws attention to the clinical white lab coats of the scientists by arranging them on the diagonal—directs viewers to imagine these medical professionals as symbols of Britain’s biomedical power, much like the illustration of Boyce and Sherrington. London is visually represented as the heart of research in the British Empire, its authority as the imperial capital bolstered by its techno-scientific prowess and specialist expertise. Indeed, the caption also tells us that the new building is “devoted to other medical research and to the teaching of the medical practitioners of the future,” painting a picture of generations of white Western scientists maintaining the strength of the Empire through the vehicle of public health. In 1938, the British Empire was still at its height and tropical medicine was burgeoning as a discipline; this kind of photograph (which was produced for general interest magazines like Tatler and Illustrated London News) would have operated as a subtle form of imperial propaganda, advertising Britain’s advances in tropical medicine to the general public. The reproduction of recognisable visual tropes like the lab coat, microscope, and studious scientist constitutes a visual rhetoric of public health that instructs viewers to imagine Britain as a dynamic biomedical power.

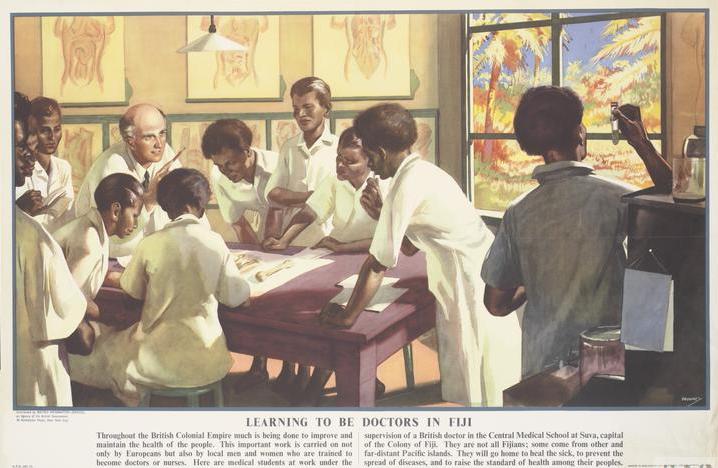

Where in the previous images the production of colonial medicine is visualized as centered in London and limited to white populations in terms of access, a lithograph poster made by John Nunney in 1945 widens the focus to Fiji, where it is suggested that colonized communities are in the process of gaining access to tropical medicine expertise. Entitled “Learning to be Doctors in Fiji,” the poster was produced for distribution in schools by the Central Office of Information for the Colonial Office (COI). It pictures a white doctor teaching a group of Pacific Islander medical students in a classroom. The caption indicates they are “in the Medical School at Suvam, capital of the colony of Fiji,” learning from a British doctor to “raise the standard of health among their peoples.” The poster makes explicit what remains latent in the previous images: the racialization of who is and who isn’t allowed to claim authority over and disseminate medical knowledge. Nunney’s image depicts a clear racial hierarchy in which the white doctor is the central authority in the room, didactically imparting medical knowledge to the younger medical students of color. The sense of cultural difference is reinforced by the tonal contrast between the somber color palette of the interior, plastered with anatomy posters, and the vibrant colors of the tropical scene outside the window. The poster implies that the serious world of medical knowledge and learning lies with the doctor inside, who will ensure that the exotic, “uncivilised” world of Fiji beyond the window is brought under the control of Britain through the supposedly benevolent paternalism of healthcare.

Yet the figures at the periphery of the poster offer another vantage point which complicates the jingoistic colonial messaging of the image. On the far right of the illustration, a young student turns away from the doctor, holding up a test-tube. He and a figure on the left side of the image—who is pictured watching him—are the only students who aren’t engaged with the white doctor’s demonstration. A reading of the poster against its colonial bias offers an alternative vision of Fiji’s future, in which the young student with the test-tube becomes the embodiment of medical authority, repurposing medical knowledge shared by colonisers to undermine the need for British medical pedagogy and the presence of British researchers. We can view the figure of the young student—or future medical researcher—as a symbol of the reality of medical knowledge sharing, in which research about tropical diseases was produced in local conditions by colonised populations, as much as it was by British scientists in the imperial capital. An alternative reading of this image helps us see how medical research fed into a global network of knowledge exchange that was transnational and reciprocal.

The circulation of the poster through schools suggests the extent to which the COI intended to medicalize Britain’s national identity in the post-war period. 1945 heralded the slow decline and collapse of the British Empire, forcing Britain to seek other expressions of global power in place of its previous imperial strength. As these three images show, tropical medicine became a useful vehicle through which Britain could justify its colonial project, naturalizing colonial discourses of race that placed white British men in positions of authority and power over non-white populations. Yet if we look a little closer, these imaginaries of Britain as a world-leading biomedical power are predicated on colonial fictions about knowledge exchange. By applying a critical gaze when viewing these visual artefacts, it is possible to resist the colonial frames of vision they uphold.

Footnotes

1 Roberta Bivins, “Coming ‘Home’ to (post)Colonial Medicine: Treating Tropical Bodies in Post-War Britain.” Social History of Medicine 26, no. 1 (2013): 1–20.

2 “The Treatment of Tropical Diseases.” The Graphic, June 17, 1899.

3 “The Treatment of Tropical Diseases.” The Graphic, June 17, 1899.

Comments are closed