Pathologies of Difference: Notes

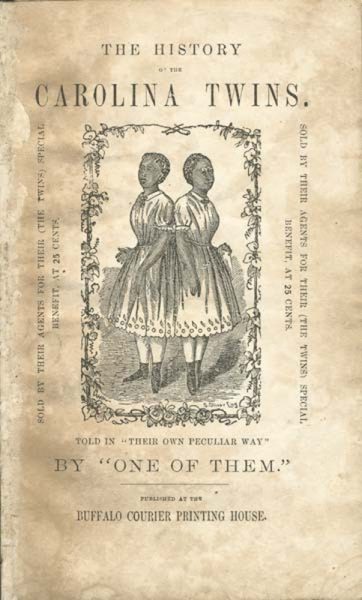

A response to Title Page Image From Mille-Christine, History of the Carolina Twins

Jessica Womack, Art Hx Team Member

Title: Title Page Image From Mille-Christine, History of the Carolina Twins: “Told in Their Own Peculiar Way” by “One of Them.” Buffalo: Buffalo Courier Printing House, 18–?.

Date: ca. 1869

Source: North Carolina Collection, University Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Read Jessica's Response

One of the first objects I found for the Art Hx project was a pamphlet telling the story of the McKoy twins, two enslaved Black women from North Carolina who were conjoined at the lower back. Often referred to as the “Carolina Twins,” Millie and Christina McKoy were born in North Carolina during the mid-19th century to an enslaved mother. Because they were conjoined, they were sold quite young and put on display throughout their infancy, childhood, and adulthood; after the end of slavery in the United States, they continued to be exhibited in what were called “freak shows” and “sideshows” across the southern US and elsewhere; they even traveled to Britain where they met then monarch, Queen Victoria.

The story of the McKoy twins highlights the ways the normative bodies of enslaved people were valued for labor and production; those with nonnormative bodies were often used for financial gain in other ways—such as the exhibitions the McKoys were shown in. This pamphlet and the depiction of the McKoys on the cover and frontispiece highlight the critical importance of considering ability and disability as we study the institution of slavery in the Americas and the myriad experiences of enslaved people. The pamphlet also underscores the wide ranging approaches enslavers took to ensure they financially benefited from the bodies of the enslaved and how influential their designations of normative and nonnormative were—and it prompts questions about how these medical, scientific, and social taxonomies even influence our contemporary world, a world too often shaped by considerations of bodies based on notions of “health” and worth.

—Jessica Womack, Art Hx Team Member

A response to A “Hottentot” woman with large labia pedendi

Sydnae Taylor, Art Hx Team Member

Title: A “Hottentot” woman with large labia pudendi.

Artist/Maker: J. Pass

Date: 1810

Source: Wellcome Collection

Copyright/Permissions: A “Hottentot” woman with large labia pudendi. Coloured engraving by J. Pass. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Read Sydnae's response

I have always been interested in the ways in which our knowledge of the past informs our present, especially in regards to our understanding of the body and healthcare. This image is particularly fascinating because it touches on the hypervisuallization and exploitation of the black female body and I continue to be curious about how Black women have been transformed into an object for others to analyze, interpret or enjoy. The term “Hottentot” was formerly used to describe a group of people of South Africa, known as Khoisan. Among these people was a woman named Sarah Baartman, called “The Hottentot Venus”, and she was exhibited in European shows for the enjoyment and ridicule of white audiences. The exaggeration of Sarah Baartman’s protruded buttocks was an area of great fascination to the white audience and similarly in this image, the exaggerated labia, called the “natural apron” is the point of interest for this artist.

Through this image and similar portrayals of the “Hottentot” woman, important observations that I have made are that not only is the history of Black women is often depicted through the white, male gaze, they have been historically used to satisfy sexual curiosities of others. As a result, I have been eager to learn more about the experiences of Black women who have often been made the subjects of art and storytelling but rarely given the chance to be the storyteller. The life of the unidentified woman in this image, or Sarah Baartman, was never told from her perspective and I believe that Art Hx has enabled me to work to amplify the voices of historically silenced women, who have been hypervisualized whilst simultaneously ignored. As I continue to research in Art Hx, I am challenged to reimagine how I think about colonial history through the lens of art and medicine and eventually develop a more holistic understanding of the Black experience. Through discovering more images, I question the identity and motive of the artists and how the work aligns with the experiences of the people that they portray. I hope to continue to find more objects that encourage me to read against the grain and develop deeper understandings of how history has shaped my perception of myself as a Black woman.

—Sydnae Taylor, Art Hx Team Member

A response to Lancet owned by Edward Jenner

Phoebe Warren, Art Hx Team Member

Title: Lancet owned by Edward Jenner

Date: 1720-1800

Source: Science Museum, London

Copyright/Permissions: Lancet owned by Edward Jenner, England, 1720-1800. Credit: Science Museum, London. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Read Phoebe's response

I don’t think I’ve given vaccines or their history much thought until about a year ago. I’ve taken two immunology classes since the start of the pandemic, and in both classes my professors presented a brief history of vaccinations. This history typically paints Edward Jenner as something of a hero, who has this light-bulb moment in which he discovers this link between cowpox and smallpox…and the next thing you know, we have vaccines! Being a part of the Art Hx project has made me skeptical of these neat narratives about medical developments. While researching this lancet, owned by Edward Jenner, I learned about inoculation, which is a process of transferring material, often the pus or scabbed-over parts of a wound, from one person to another. Inoculation was commonly practiced in China, India, and parts of Africa and the Middle East well before Mary Wortley Montagu witnessed the procedure in Turkey in 1721 and brought her knowledge of it to England. Inoculation against smallpox involved scraping this material off of the body of a person infected with smallpox and, after using a lancet to break the skin, transferring it directly into the body of an uninfected person. The inoculated person would often get mildly sick, but the hope was that they would survive and then have lifelong immunity against the disease. Beginning in the 1720s, British physicians began to conduct medical experiments with inoculation. For example, physicians performed inoculations on incarcerated people in London’s Newgate Prison, who were rewarded with freedom for serving as test subjects.

During and after a smallpox epidemic in 1768, British physician John Quier conducted medical experiments on a population of about 2,000 enslaved people in the Worthy Park sugar plantation in rural Jamaica. Inoculation benefited the plantation economy by preventing enslaved people from getting severely ill. But Quier’s experiments actually caused his patients greater harm than a mild case of smallpox. He used methods that would never have been allowed on European patients in order to further his professional reputation. He sent letters to his friend and physician Donald Monro that describe in detail how he inoculated pregnant women and patients already suffering from painful diseases such as yaws and fevers, and how he performed inoculations on the same patients again and again. Monro in turn read these letters aloud to audiences at the College of Physicians in London, and later published their contents in 1778. John Quier also mentored James Thomson, who conducted inoculation experiments on enslaved people in Jamaica. Quier is just one story among many that are often left out of the history of vaccinations as it is told in science classes and other contemporary contexts.

The presence and violence of the lancet is felt throughout Quier’s meticulous documentations of the disease experiences of his patients. Finding this lancet, owned by Edward Jenner, made me think about the embodied experience that Quier’s letters describe in a totally different way.

—Phoebe Warren, Art Hx Team Member

Bibliography

Boylston, Arthur.“The Origins of Inoculation.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 105, no. 7 (2012): 309-313.

Schiebinger, Londa. Secret cures of slaves: people, plants, and medicine in the eighteenth-century Atlantic world. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press (2017), 11.

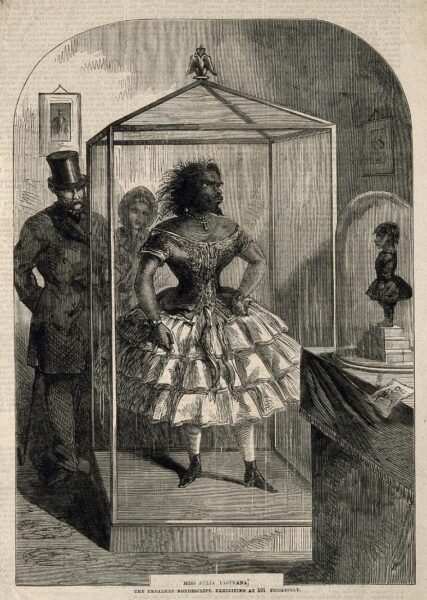

A response to Julia Pastrana, a bearded woman, embalmed

Bhavani Srinivas, Art Hx Team Member

Title: Julia Pastrana, a bearded woman, embalmed

Date: 1862

Source: Wellcome Collection

Copyright/Permissions: Julia Pastrana, a bearded woman, embalmed. Wood engraving, 1862. Public Domain Mark

Read Bhavani's response

In this image, a wood engraving, the embalmed body of a woman is displayed in a decorated glass case inside a gallery. Her body is hairy and posed in a dress with a tight corset. Well-dressed visitors walk through the gallery and observe her body. A caption reads: “Miss Julia Pastrana, the embalmed nondescript, exhibiting at 191 Piccadilly.”

Julia Pastrana was a woman from Mexico whose hairy face and body made her a popular attraction in carnivals and what were called freak shows throughout the U.S. and Europe during the mid-1800s. This wood engraving was printed after Pastrana’s death to publicize the exhibition of her embalmed body in a gallery in London in 1862.

I first read about Julia Pastrana in Plucked: A History of Hair Removal, by Rachel Herzig. I came to Herzig’s book through the work of Alok Vaid Menon, a trans writer, performer, and speaker whose work I have admired and learned from for a while. In the chapter “Bearded Women and Dog-Faced Men: Darwin’s Great Denudation,” Herzig describes how people, like Pastrana, who were considered abnormally hairy by the Euro-American public were displayed and publicized as sub-human examples of the “missing-links” proving Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. Advertisements described Pastrana as a descendent of a “race of savages,” and also speculated that she had an orangutan or a bear for a parent.

I was disturbed to find this image. Even immediately after Pastrana passed away, the people who profited from displaying her as a novelty were eager to promote the inspection of her body in a gallery. This event reveals the close ties the institution of the museum had with carnivals and freak shows. The way that Pastrana’s body was shown off, encased and put on a pedestal, is an example of how conventional strategies of display, though they might otherwise seem neutral, have potential for violence. The intertwining of our museums with the harm of scientific racism, has not been fully reckoned with.

—Bhavani Srinivas, Art Hx Team Member

Bibliography

Herzig, Rebecca M. “Bearded Women and Dog-Faced Men: Darwin’s Great Denudation.” In Plucked: A History of Hair Removal, 55-74. NYU Press, 2015.