By Shelley Saggar, 2022-2023 Art Hx Interpretive Fellow

John Bell and Croydon Ltd., ‘Prorace’ Cervical Cap, ca. 1915-1925, designed by Marie Stopes. Courtesy of the Science Museum Group Collection. Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0)

A round, rubber object stamped with a curious message offers a route into excavating the connections between medical and reproductive education, religious conversion, and family history in this constellation. The phrase “PRORACE” is printed onto a contraceptive cap, a design adapted by Marie Stopes (1880– 1958), a British birth control campaigner. Stopes was largely interested in reproductive education and access as a result of her commitment to eugenics, a pseudo-scientific theory of human hierarchy that was mapped onto a belief in so-called “selective breeding.” Setting up shop at the Mother’s Clinic in London, she focused on ensuring that her message and methods were disseminated in both the slums of the city’s East End and further overseas. Both regions, in her mind, were at risk of being “swamped by hordes of Indians and Chinese.”[1]

While Stopes is widely celebrated, the text printed on this object offers a potent reminder of the colonial underpinnings of movements for medical—especially reproductive—education, particularly as these have often been directed at racialized and poor women throughout history. By way of example, in London’s Science Museum, where the contraceptive cap is currently displayed, an online description of the object acknowledges Stopes’ eugenicist motivations, but insists that Stopes is “best remembered as a feminist and a birth control pioneer”—a framing that dismisses her racialist fervor as an awkward asterisk in an otherwise progressive narrative of medical history.[2]

This narrative of progress and women’s empowerment can be tricky to counter from a critical perspective, particularly in a climate of heightening political restrictions on reproductive rights. Yet situating this object in the context of enduring colonial narratives that undergird the stories we tell about health and medicine helps to understand the colonial history it belongs to. While Stopes’ approach to reproductive technology can be seen as a direct intervention in women’s health and medical education, British colonialism often adopted quieter methods of coercion through religious conversion and epistemic imperialism.

In the late nineteenth century, Dr. Edith Brown, a medical missionary from Cumbria, set up the North India School of Medicine for Christian Women—the first medical college for women in India.[3] Founded in Ludhiana, Punjab in 1894, almost thirty years before the opening of Stopes’ Mother’s Clinic, the school ascribed to a narrative of benevolent paternalism that guided Dr. Brown’s missionary work—a conviction that was not so distant from Stopes’ own framing of Indians as “the backward peoples” of the world.[4] Brown felt a need to train native women in medicine, particularly midwifery, due to what she viewed as the “ignorant” and “superstitious” practices of the dais (local midwives).[5] While Brown’s concerns were derived from her medical education (in contrast to Stopes—and others’—commitment to the pseudo-science of eugenics), her dismissal of Indigenous womens’ medical knowledge and her fervent belief in the power of “Conquest by Healing” affirm the complicated entanglements between medical education, religious conversion, and racial hierarchy in the colonial operation.[6] The school initially only trained Christian girls, with the stipulation that prospective scholarship applicants “must undertake to work in some Protestant Mission to the Heathen after the completion of their course of study.”[7] This framing illustrates the so-called “civilizing mission” that undergirds both Stopes’ direct interventions in reproductive education and colonial influence in the arena of medical education and women’s health more broadly.

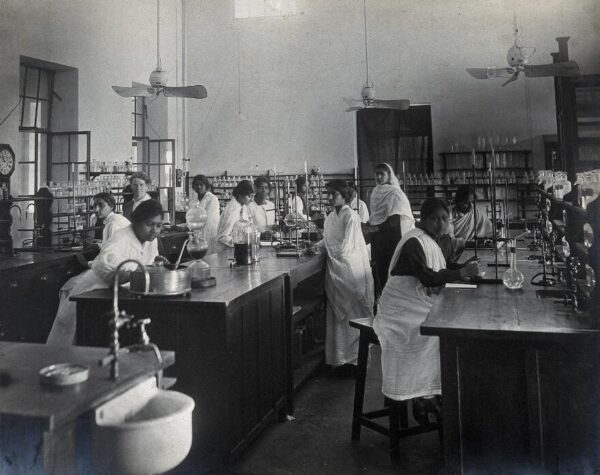

Lady Hardinge Medical College and Hospital, Delhi: women students in a laboratory. Unknown photographer, 1921. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection. Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

Yet in spite of this, a rich vein of resistance runs through the college’s archives. Writing in 1898, Dr. Brown herself commented on the difficult case of a patient who, despite the best efforts of the missionaries, refused to yield to Christian doctrine. Instead, the patient regaled staff, students, and the sick with tales of her life “[b]efore the Mutiny” when “she and her mother were dancers before the King of Delhi.”[8] There is a note of admiration in the doctor’s otherwise stern assessment, compounded by a wry speculation that perhaps the patient’s refusal to accept Jesus was partly due to her fondness for imbibing opium and her habit of smoking via a hookah pipe, both of which she would have been hard-pressed to quit in the name of salvation.[9] Local midwives, too, remained “unimpressed” and refused to attend lectures at the college until Brown eventually offered first a payment for attendance and subsequently a remittance “for requesting her assistance.”[10] These instances signal quiet but firm refusals of the assumption of Western medical supremacy. Their remnant presence in the archives stands as testimony to even the missionaries’ acknowledgement of the power of these women.

These histories come to light in an image of students at Lady Hardinge Medical College and Hospital, another medical training facility for women. The photograph depicts a group of girls standing in a medical laboratory. Their serious expressions and starched white saris remind me of my late grandmother, Zeenat Alfred, despite the fact that the photograph was taken before she was born. My grandmother enrolled as a pupil at Ludhiana Christian Medical College (as Dr. Brown’s North India School for Christian Women came to be known) and such was her admiration for the college’s missionary founder that she proudly named my mother after “Dr. Edith.” Despite the dismissal of Indigenous knowledge and the assumption of Western “civilizational” supremacy by medical missionaries, religious conversion, for many like my grandmother, offered an escape from the constraints of class and caste through an education that would have otherwise been denied to them. Yet notwithstanding her Christian faith, she continued to incorporate local knowledge into her nursing practice throughout her life—an act that can be read as a continuation of the refusal recorded in the archive.

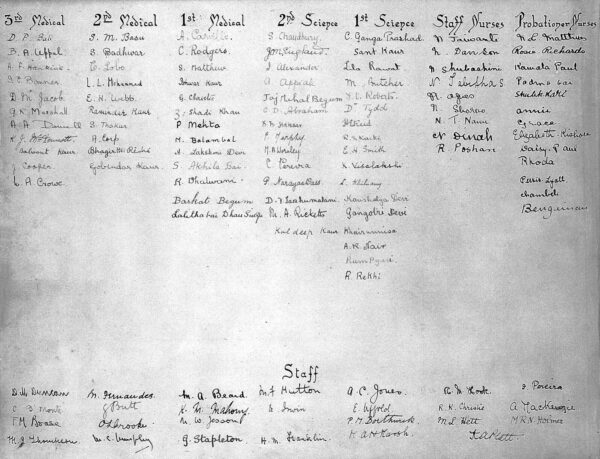

A handwritten list accompanies the photograph, a record of students and staff at Lady Hardinge Medical College in the year 1921—the same year that Marie Stopes opened the Mother’s Clinic in London. Looking at the list, the personal stories of colonization, conversion, and women’s medical education are brought into sharp relief. Amongst the Kaurs, Begums, Devis, and Khans recorded as pupils are a smattering of English names: Abraham, Jacob, Matthew. Almost without thinking, and even though I know it won’t be there, I still scan for my grandmother’s name, Alfred.

Lady Hardinge Medical College and Hospital, Delhi: list of students and staff at the hospital, ca. 1921. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection. Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

Footnotes

[1] Marie Stopes, q. in Ruth E. Hall, Passionate Crusader: The Life of Marie Stopes (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1977), 291.

[2]‘“Prorace” Cervical Cap | Science Museum Group Collection

[3]Catharine M. C. Haines, and Helen M. Stevens, “Brown, Edith Mary,” International Women in Science: A Biographical Dictionary to 1950 (ABC-CLIO, 2001), 45.

[4] Stopes, q. in Hall, Passionate Crusader, 291.

[5] Edith M. Brown, “An Introduction to Ludhiana” (Women’s Christian Medical College, Ludhiana, 1930), MS 381189, Box 2, Ludhiana Medical College, SOAS Library Special Collections, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 8.

[6] “Conquest by Healing,” (London: Medical Missionary Association, 1957), MS381189, Box 2, Ludhiana Medical College, SOAS Library Special Collections, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

[7] Prospectus of the North India School of Medicine for Christian Women, (North India School of Medicine for Christian Women, 1900-1901), MS 381189, Box 1, Ludhiana Medical College, SOAS Library Special Collections, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 36.

[8] Report of the Ludhiana Women’s Christian Medical College, Punjab, India, 1898-99, MS381189, Box 1, Ludhiana Medical College, SOAS Library Special Collections, School of Oriental and African Studies, London, 11 (hereafter cited as Report of the LWCMC, 1898-99); The Indian Mutiny of 1857, also known as the First War of [Indian] Independence, was an uprising against the East India Company.

[9] Report of the LWCMC, 1898-99, 11.

[10] Maureen Pritchard, ‘A Very Great Medical Missionary’ in Conquest by Healing, 1957, MS381189, Box 2, Ludhiana Medical College, SOAS Library Special Collections, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 4; Haines and Stevens, International Women in Science, 45.

Comments are closed